The textile artist Annie Albers

Hanne Loreck

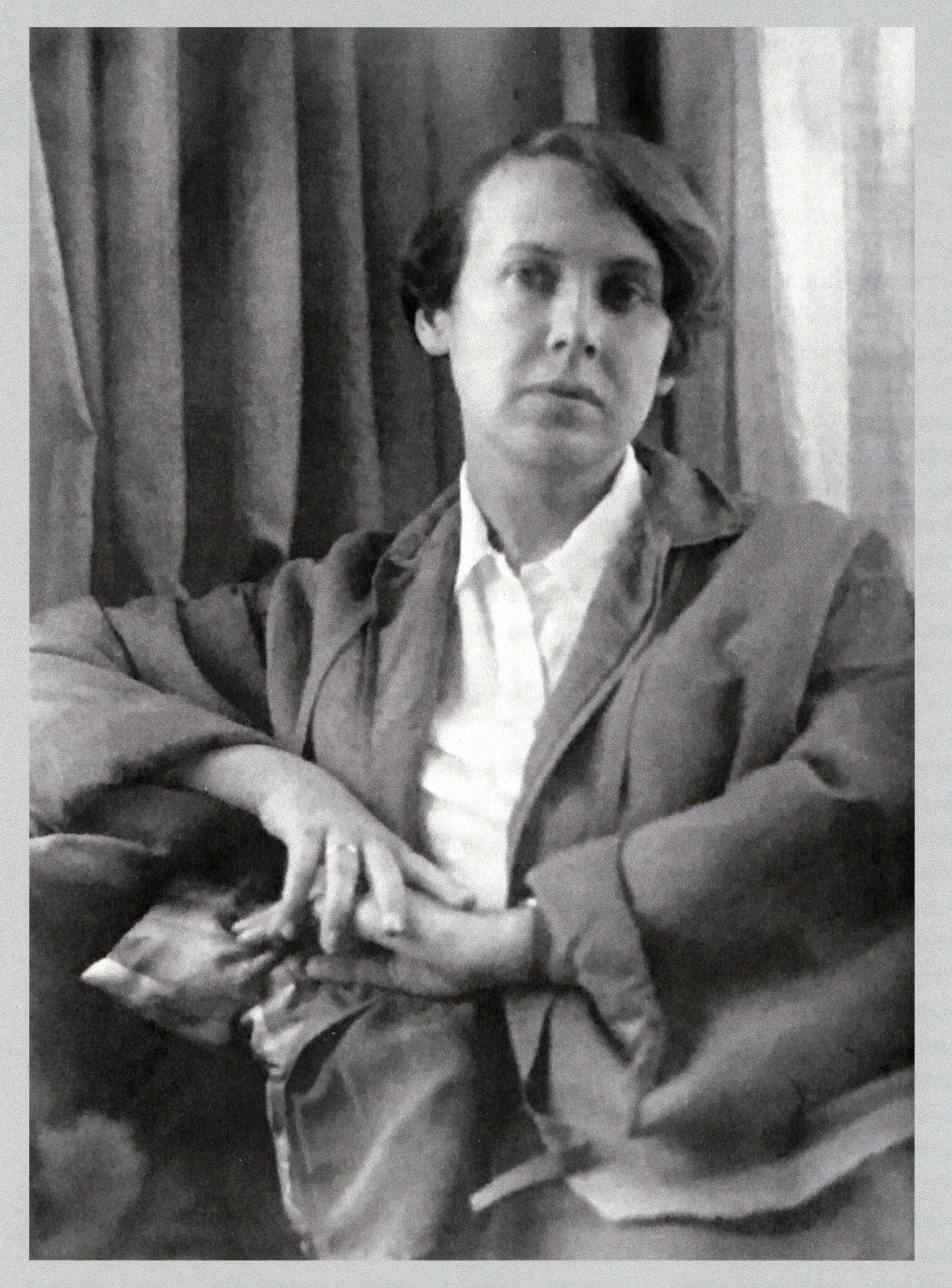

Portrait of Anni Albers, 1927, repronegative, 1960s; Photo: Lucia Moholy; © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin

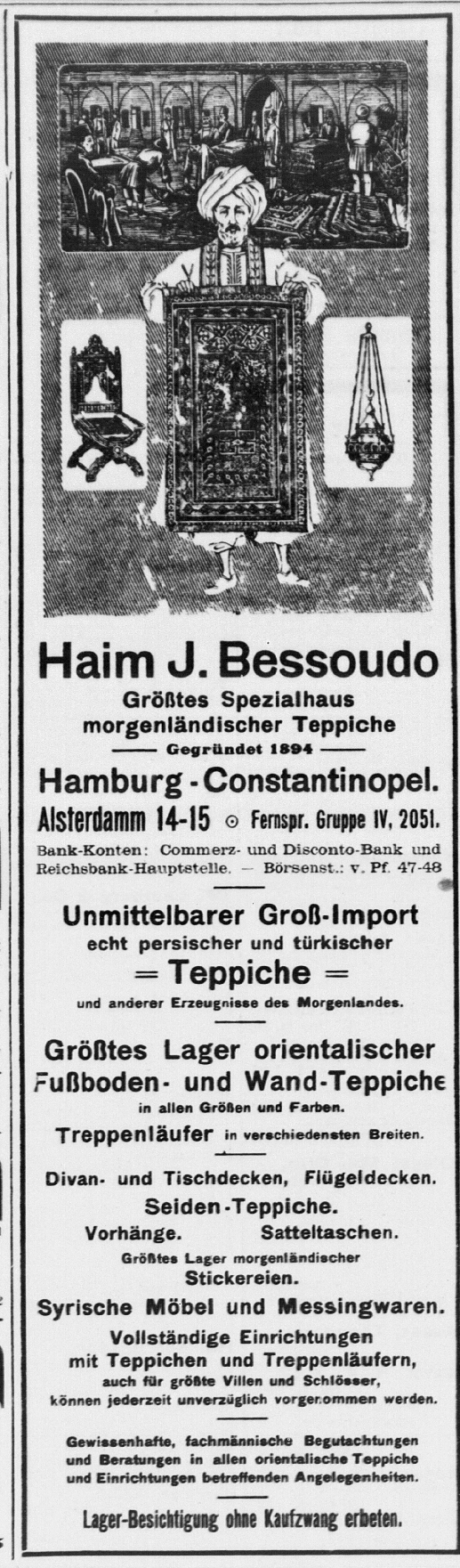

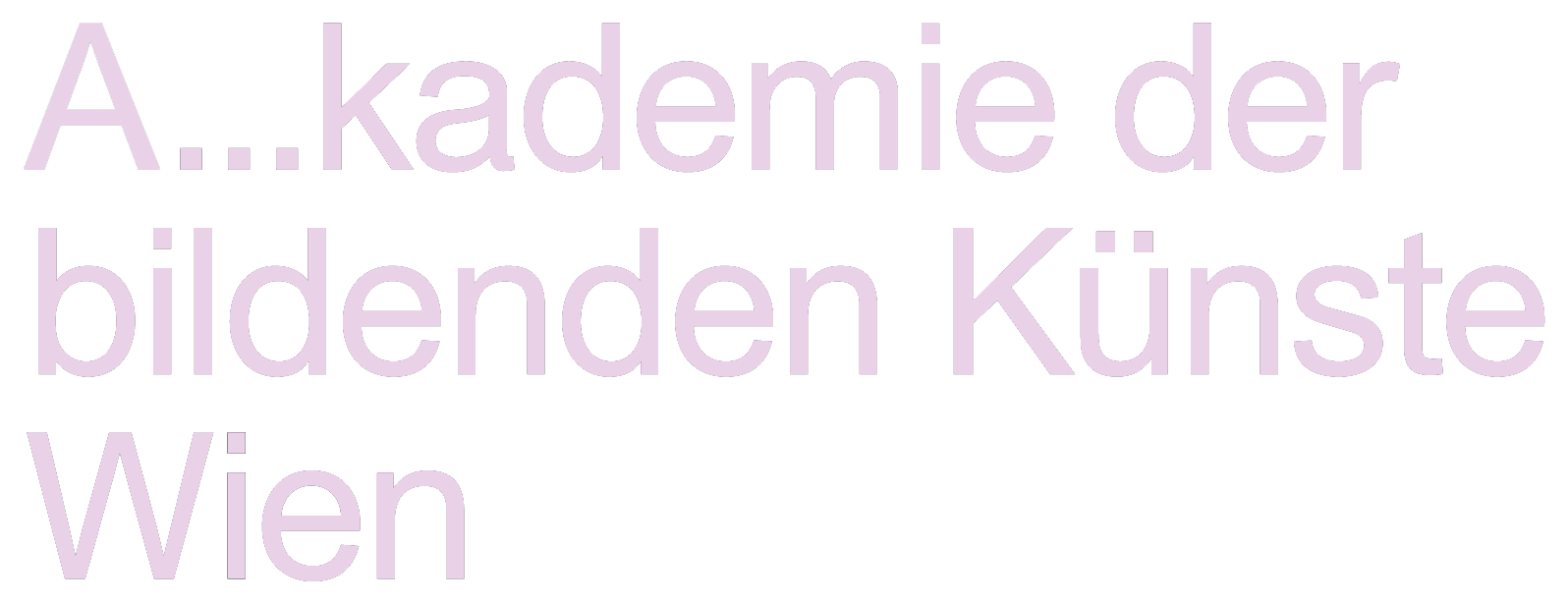

The following essay reconstructs the 1921–22 academic year that Anni Albers, still Annelise Else Frieda Fleischmann (1899–1994; she married Josef Albers in 1925), spent at the Staatliche Kunstgewerbeschule zu Hamburg [Hamburg State School of Arts and Crafts], immediately prior to her legendary period of study at the Bauhaus. My research is based on relatively sparse archival materials, which nevertheless enable some adjustments to be made to the apparently dependable biography of this renowned weaver, textile artist, designer, printmaker, university lecturer, and theoretician. 1

Above all, however, I attempt to address the potentials and problems raised by an arts and crafts school of this period through the individual experience voiced by Albers in her predominantly late memoirs and in art historical monographs. This enables me to speculate on why the symbolic capital of applied art schools, which was and still is considerably lower than that of art academies, is perpetuated into the biographies of women artists. The Bauhaus was founded in 1919 with the programmatic claim to abolish the clear-cut separation between applied and fine arts and thereby to realize a visionary curriculum, also in the sense of gender equality. This radical new theory and practice of design aimed to remodel ‘outdated’ applied arts towards an innovative approach to handicraft and industrial production. If little attention has been paid to Anni Albers’ year of study in Hamburg, this, on the one hand, has to do with the powerful, even mythical dimension of the art historiography of the Bauhaus as an institution. In order to establish and consolidate this myth, the school of applied arts, which figured as the most recent structural forerunner in this particular field of education, had to be portrayed as directly overtaken by history, therefore antiquated, or be bluntly suppressed. Here, on the other hand, a gender dispositive is at play. Until well into the 20th century, women had no opportunity to enroll in academic art training in the disciplines of painting or sculpting. Denied access to public art academies, they were left to study art at the few women’s painting schools run by women artists’ associations, or more commonly at––costly––private art schools. Even at a public school of arts and crafts such as the Hamburg institution, women students were only admitted from April 1907––not exactly early. 2

Just over a decade later, around 1920, applied arts were already received as the domain of women––and had thus lost cultural prestige and aesthetic worth. This differed from the situation in the second half of the 19th century, in which the promise of modernism to infuse everyday life with art and to implement ‘artistic culture’ had enhanced the reputation and contemporary relevance of the arts and crafts, even from the perspective of ‘fine artists’. But with the significant change of socio-political circumstances that prevailed in 1921, this modernism had already well passed its halfway mark 3 : women had only recently been granted the right to vote, the First World War was barely over, and, from the onset, the social and cultural awakening promised by the Weimar Republic and its parliamentary democracy was tainted by fiercely opposed political battles.

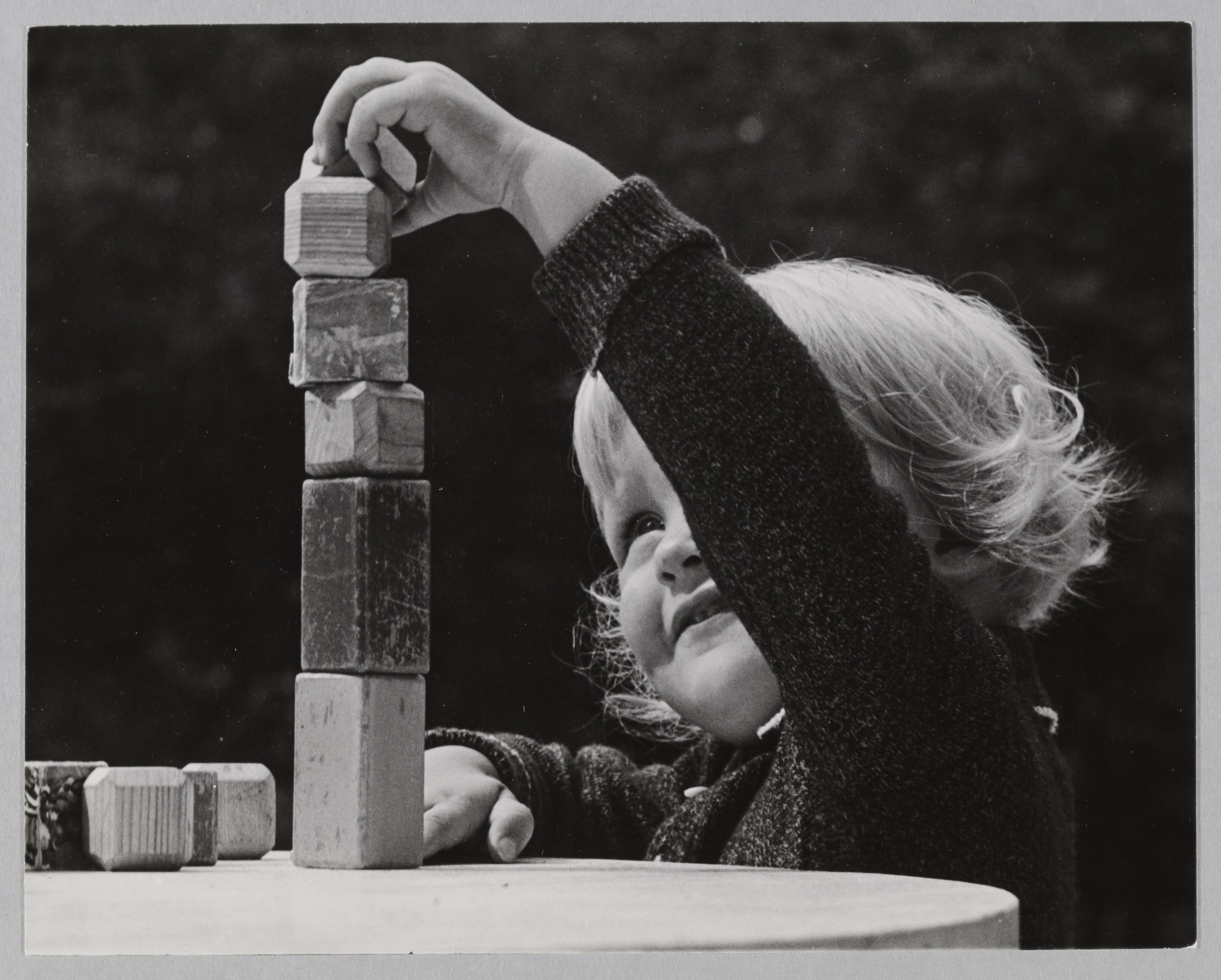

Coming from a privileged background––her mother from the German-Jewish Ullstein publishing family, her father from a German-Jewish mirror glass dynasty and himself a furniture manufacturer––Annelise 4 Fleischmann was encouraged in her artistic interests at an early age. Her mother hired a house tutor for art lessons, 5 and from 1916 the young woman attended courses in painting with Martin Brandenburg (1870–1919) at the Studienateliers für Malerei und Plastik 6 taught Anni––the Studienatelier(s) für Malerei und Plastik––was exclusively for young women.” (Weber 2020, p. 57). Photographs, however, show mixed-gender students sculpting in front of models of both sexes. See: lewin-funcke.de/lewin-funcke-schule.html, last accessed 7 March 2021. Arthur Lewin-Funcke’s granddaughter, Katrin Weyert, recounts that her grandfather had deliberately set up “gender-neutral” classes (email to the author, 16 March 2021). A further inconsistency in the statement that Annelise Fleischmann took classes there between 1916 and 1919 is that, due to illness, Martin Brandenburg taught at the Studienateliers only until the summer of 1918. She therefore can hardly have taken classes with him up until 1919. See: Detlef Lorenz, “Martin Brandenburg”, Allgemeines Künstlerlexikon, vol. XIII, 1996, p. 609; last accessed 10 March 2021.], a private art school. But it was the intermezzo of Oskar Kokoschka’s rejection of her application for painting––the painter had moved to Dresden in 1917 where he was appointed professor at the art academy in 1919––repeatedly referenced in Anni Albers’ biography, that took her to Hamburg: “An attempt to take classes with Oskar Kokoschka failed; he told her she would do better to become a housewife and mother. 7 It is then that she applied to the School of Arts and Crafts in Hamburg where she spent two boring semesters in an embroidery course.” 8 Her move to Hamburg may be interpreted as an indication of her desire to study ‘fine art’ painting and at the same time of her irritation at the seemingly boundless freedom of expression offered by painting. In addition, the pressure of expectations on a young bourgeois woman’s domestic vocation for her future role as a married lady of society and mother 9 fortune.” Cited after: Asbaghi 1999, p. 153.] should not be underrated. Another conceivable influence could have come from her father’s furniture business and associated questions of design. In 1968, at nearly seventy years of age, Anni Albers explains and emphasizes the challenge and potentials of materials: “And also I was at that time interested in painting and I felt that the tremendous freedom of the painter was scaring me and I was looking for some way to find my way a little more securely . . . And I find that a craft gives somebody who is trying to find his way a kind of discipline. And this discipline was driven in earlier periods through the technique that was necessary for a painter to learn. In the Renaissance they had to grind their paints, they had to prepare their canvas or wood panels. And they were very limited really in the handling of the material. While today you buy the paint in any paint store and squeeze it and the panels come readymade and there is nothing that teaches you the care that materials demand.” 10 At the same time, Anni Albers distances herself from the early stages of her artistic biography and reminisces about her two initial experiences as a student: “I had been to an art school and an applied arts school in Germany, which I felt were very unsatisfactory.” 11 Almost 30 years later, in 1999, we read: “In 1920 [sic! 1921/22; figure 1 and 2] Albers attended the Kunstgewerbeschule (school of applied arts) in Hamburg. After two months she was disappointed with the learning program and sought out other sorts of instruction.” 12 Nicholas Fox Weber, executive director of the Josef & Anni Albers Foundation for over three decades, had already in 1989 literally embellished the nature of her disappointment to a near caricature: “ . . . however, two months spent on floral wallpaper designs where more than enough for her.” 13 Likewise, in his most current publication on the life and work of the Albers’––Anni & Josef Albers. Equal and Unequal, 2020––the author merely reiterates the brevity of her studies in Hamburg together with her skepticism towards the assignments: “Anni went to the school in Hamburg for two months. She was restless there, calling it ‘sissy stuff, mainly needlepoint.’” 14 The rhetoric is certainly pointed and yet it does bring to light the conditions and implicit problems of an individual quest for an arts and crafts school after the First World War and more specifically those concerning Annelise Fleischmann’s direct learning environment. Her “Zeugniszettel” [credentials card]––such is the heading of the original document––shows that she took part in Friedrich Adler’s teaching program for two semesters, namely the “class for ornamental art” with 42 hours a week. She completes both semesters with the best grade in diligence; in each, she is certified as making good progress (grade 2); in her second semester, her initially satisfactory (grade 3) performance increases to good (grade 2). 15 In March 1918, Adler (1878-1942, murdered in Auschwitz) had been prematurely released from military service for health reasons and resumed his post at the institute as “urgently needed” 16 in a war-affected and reduced teaching schedule. Only one year after the inauguration in 1913 of the new Schumacher building of the School of Arts and Crafts, a reserve hospital with 200 beds had been established there and was to remain in operation until March 1919. 17 However, it must not only have been a matter of bridging teaching restrictions or the interruption of classes. Far more, the cultural and social climate in combination with the economic premises for a commercially successful cooperation of the arts and crafts with industry and private assignments had been subject to momentous changes. Is it then surprising that for an ambitious young woman like Annelise Fleischmann any explicit reference to the techniques, products, and patterns of the arts and crafts dating back to the beginning of the century would literally and figuratively seem anachronistic, boring, and a waste of time? Was she familiar with Ornament and Crime (1908), Adolf Loos’ polemical and fundamental rejection of functionless ornament and applied decoration? Was she, on the other hand, aware of artist Hannah Höch’s (1889-1978) call to reform women’s widespread handicraft practices––and had received it skeptically? Perhaps she was simply in the wrong category of addressees for studying arts and crafts: too upper-middle-class and too rebellious? Höch, who studied at the School of Arts and Crafts in Charlottenburg and then at the Berlin Arts and Crafts Museum Institute, earned a living by working three days a week at the handicrafts department of the Ullstein publishing house. In an emancipatory activist tone, she writes in her essay “Vom Sticken [On Embroidery]”, 1918: “Just as it does not suffice in painting today to replicate naturalistic little flowers, a still life, or a nude, so certainly must an abstract sense of form, and with it, beauty, feeling, spirit, even soul come into future embroidery . . . But you, craftswomen, modern women, who believe that your spirit is in your work, who are determined to lay claim to your rights (economic and moral), who deem your feet are firmly planted in reality, at least y-o-u should know that your embroidery work is a documentation of your own era.” 18 Höch thus takes up the reform impulse from around 1900 for the applied arts, emphasizing the aesthetic dimension of textiles, especially embroidery, in an individual and challenging manner, and sets it against mass-produced mechanical handiwork. Her appeal implies opposing this ‘new’ embroidery to the comparatively conventional social understanding of the role of a craftswoman. In 1911, embroidery as a manual and mechanical skill in artistic design for the decoration of home and dress and to form the taste of vendors in the clothing industry was still the parole of the director of the Kunstgewerbeschule Hamburg, Richard Meyer, as the way ahead in the training of arts and craftswomen. This, however, was already outmoded in two senses. 19

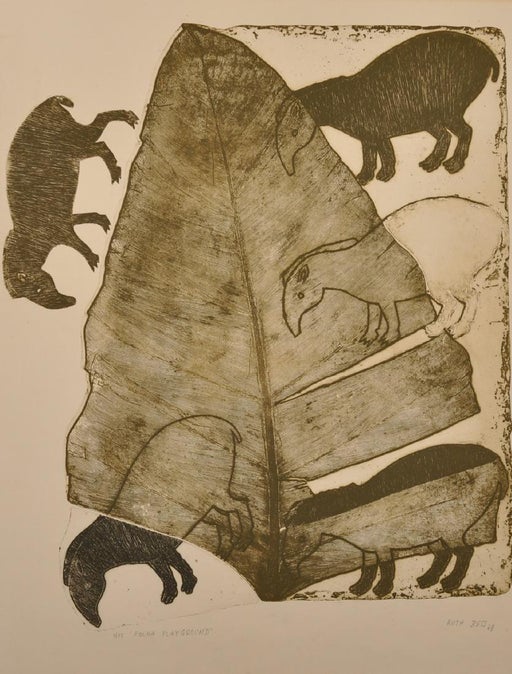

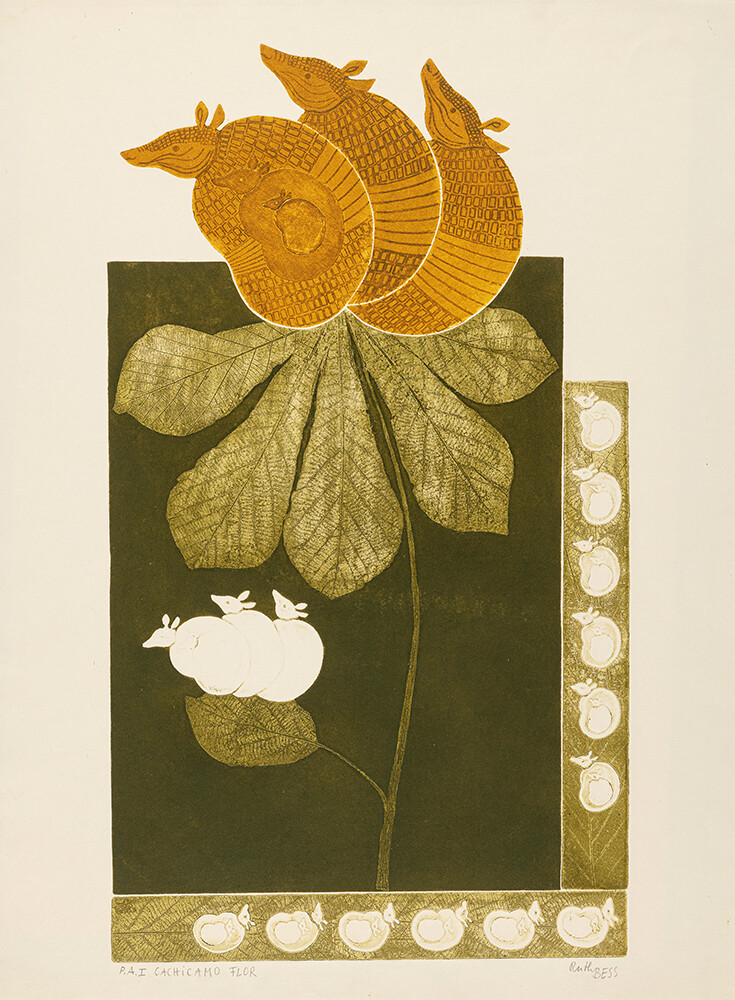

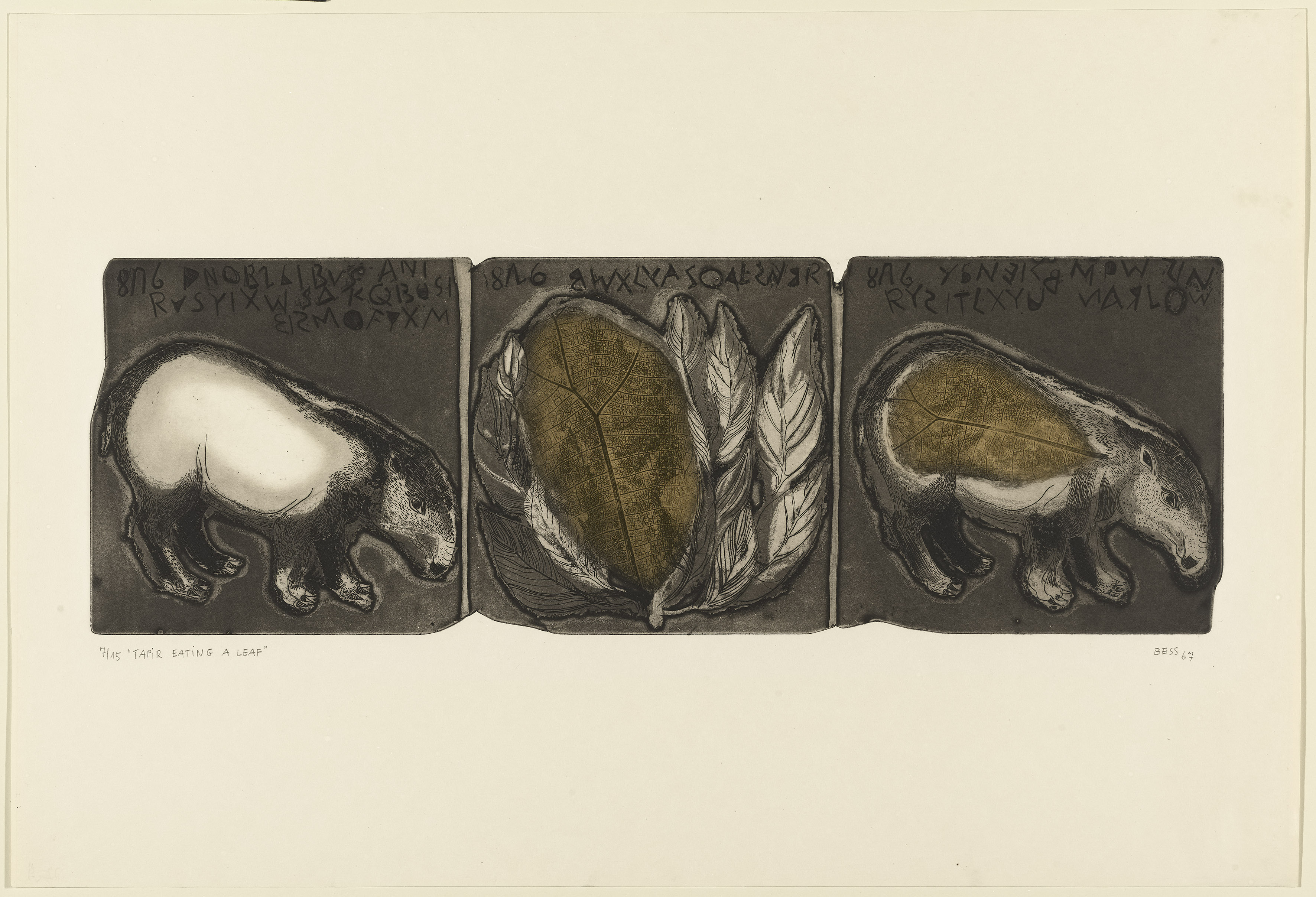

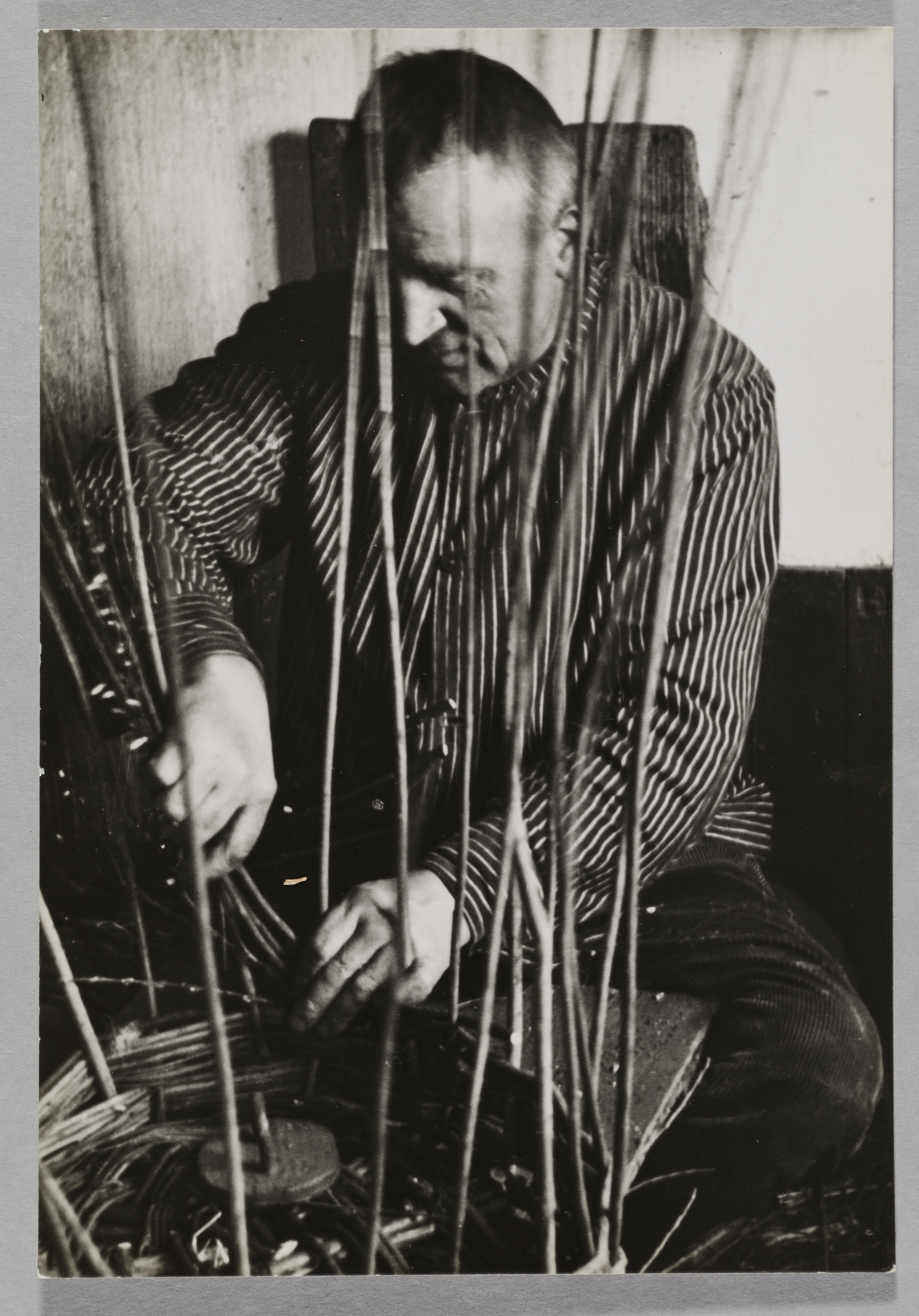

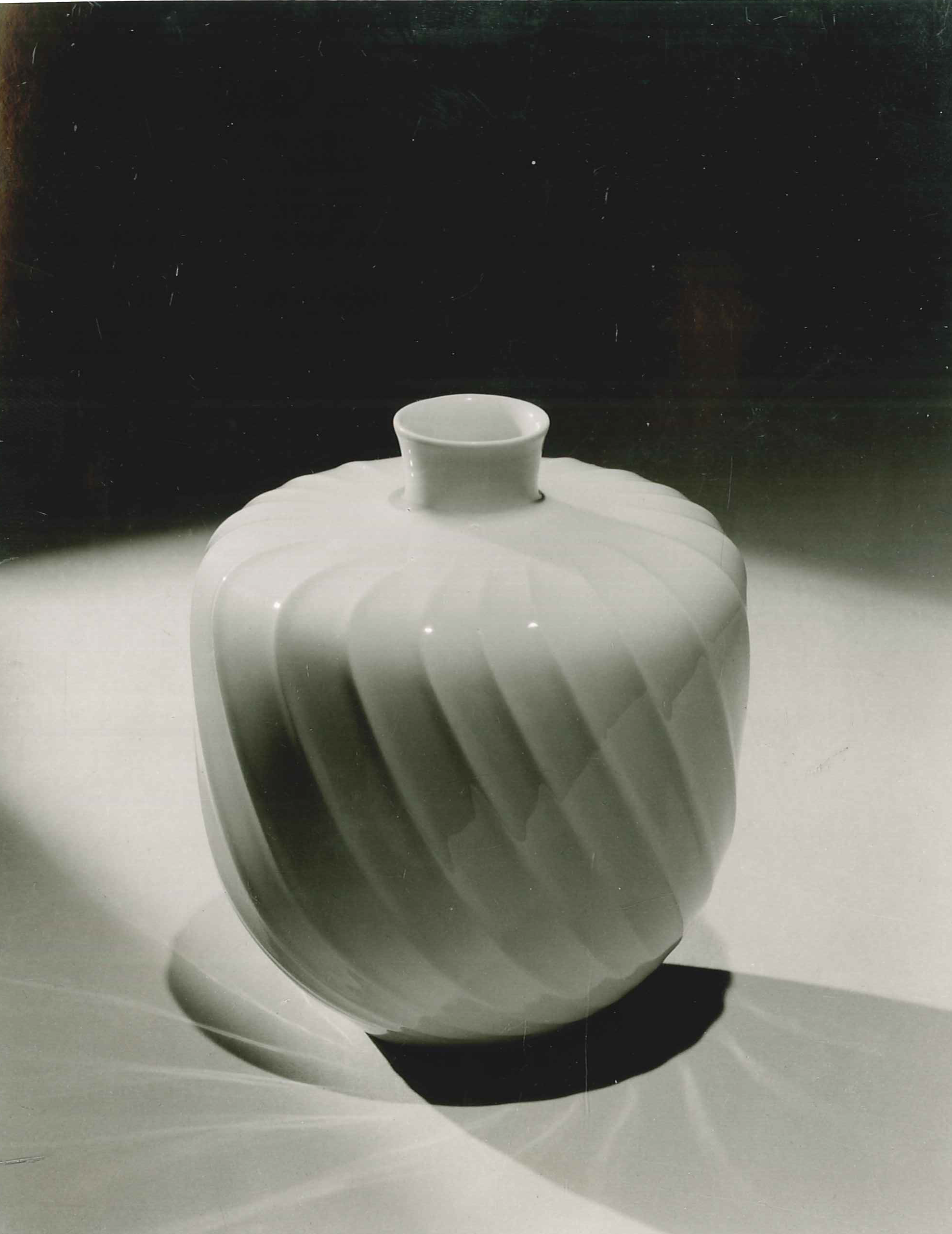

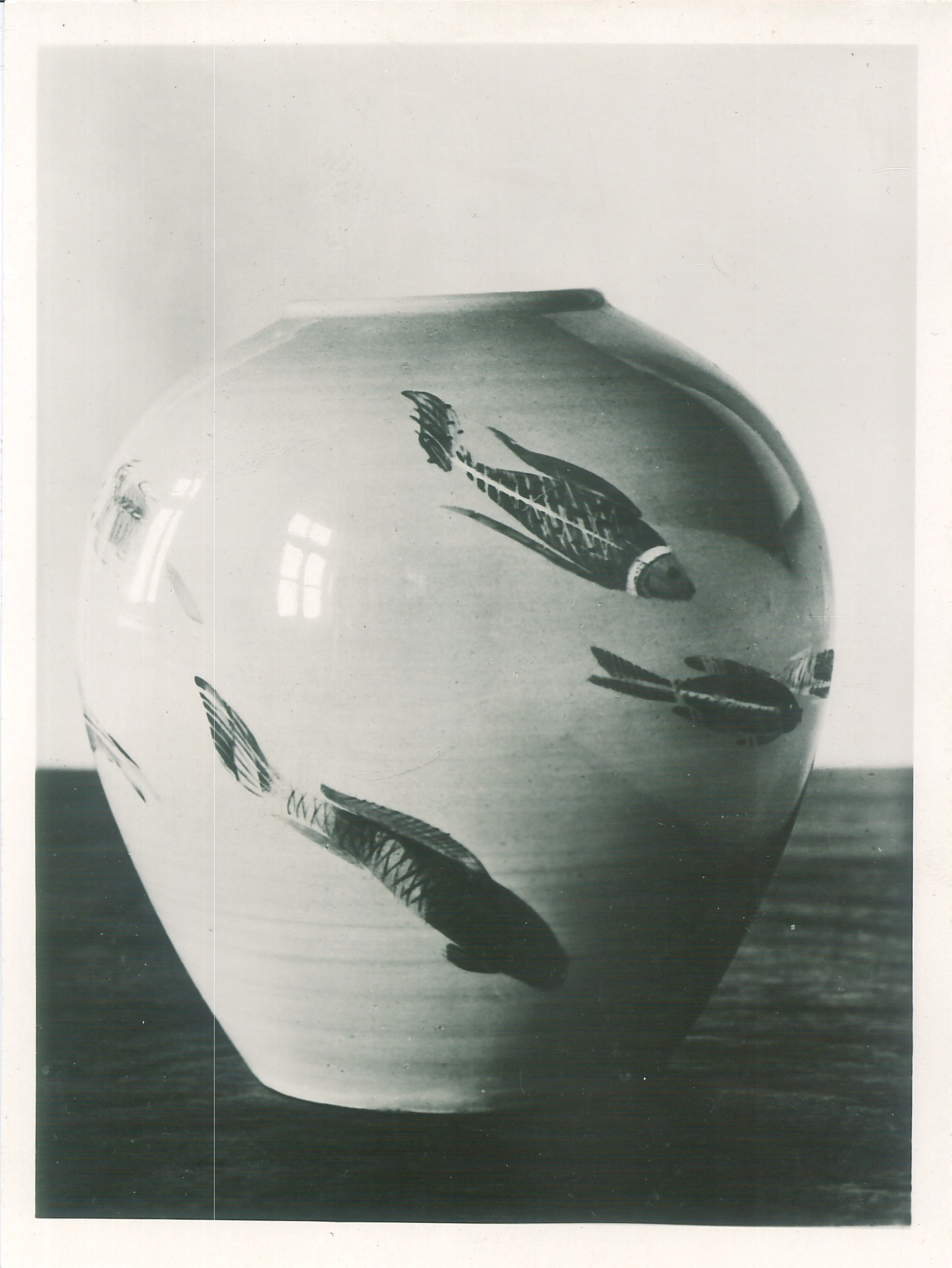

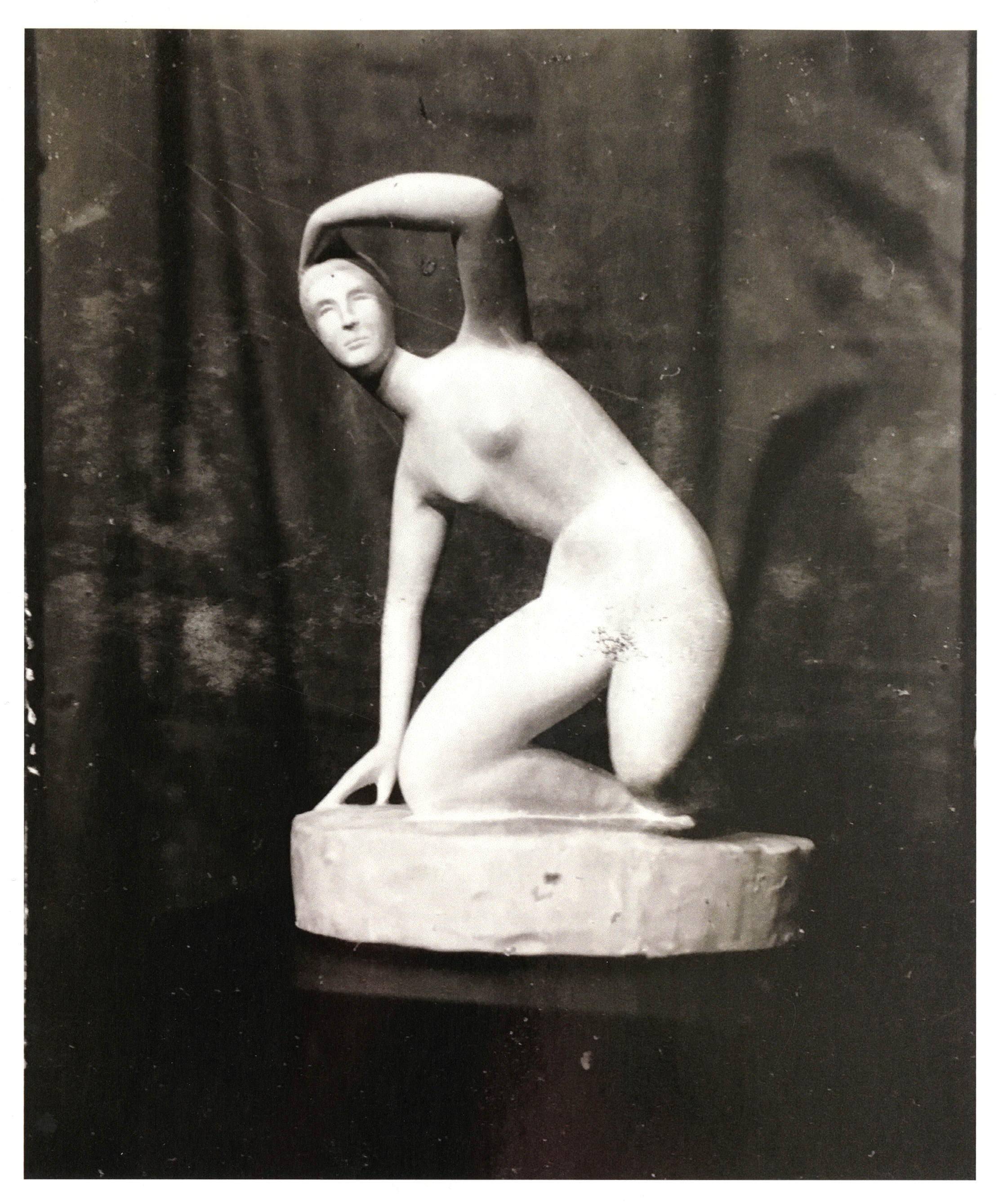

At the beginning of his career in the first years of the 20th century, Adler had worked with utility textiles for his interior designs as a freelance craftsman and as a teacher, conceiving patterns for upholstery fabrics, curtains, wallpaper, carpets, and floor coverings, but much of this was not executed until after the First World War. 20 For Adler, textiles were Initially rather marginal––his major areas of activity focusing on the design of furniture, interiors, tombstones, ceramics, and precious metalwork––in his early years in Hamburg he is even mentioned as a ‘sculptor’ 21 ” (1907–1933), in: Brigitte Leonhardt et al. (ed.), Friedrich Adler zwischen Jugendstil und Art Déco, catalogue of the eponymous exhibition at Münchner Stadtmuseum, Stuttgart 1994, pp. 412–424, p. 412.] ––but after 1920, at the time of Annelise Fleischmann’s studies, textiles are the predominant focus. 22

Adler, now confronted with a very young, mainly female generation of first year students with basically no artistic or vocational experience––Annelise Fleischmann’s fellow students are on average 17 years old and come straight from school 23 ––remains true to his credo of distilling natural forms from the study of flora and fauna for the creation of surface decor in the sense of a ‘design of timeless relevance’ 24 ; this was also in line with the increasing didactic importance of the basic curriculum for the very young students. Perhaps it is this type of exercise that Anni Albers summarizes in her recollections of the time in Hamburg as “floral wallpaper”. 25 From 1919, Adler––and there is little evidence for this period––is said to have “instructed his students a good deal more in ornamental design and enthused them for the practice of textile printing.” 26 If we follow the art historian Jutta Zander-Seidel, batik was revived in the Adler class after 1918, both as an expressive drawing technique and well adapted to the emergency mode of the time as an undemanding method of design in reference to its material and spatial requirements. 27 Aesthetically, Zander-Seidel concludes that Adler’s late work is formally characterized by an “ambivalence between closeness to nature and abstraction that never leaves the representational realm and subordinates his textile works . . . to the all-time determinants of stylization in the real world.” 28 Those innovative and historically radical new fabric textures which were soon developed by Annelise Fleischmann and her colleagues in the Bauhaus weaving class––with traditional and contemporary materials in both classical and experimental weaving techniques, unfolding their decorative effect in the graphic and geometric surface variance rather than in the pattern print––do not emerge from the considerations of form conveyed to Annelise Fleischmann in the relevant Hamburg period. 29

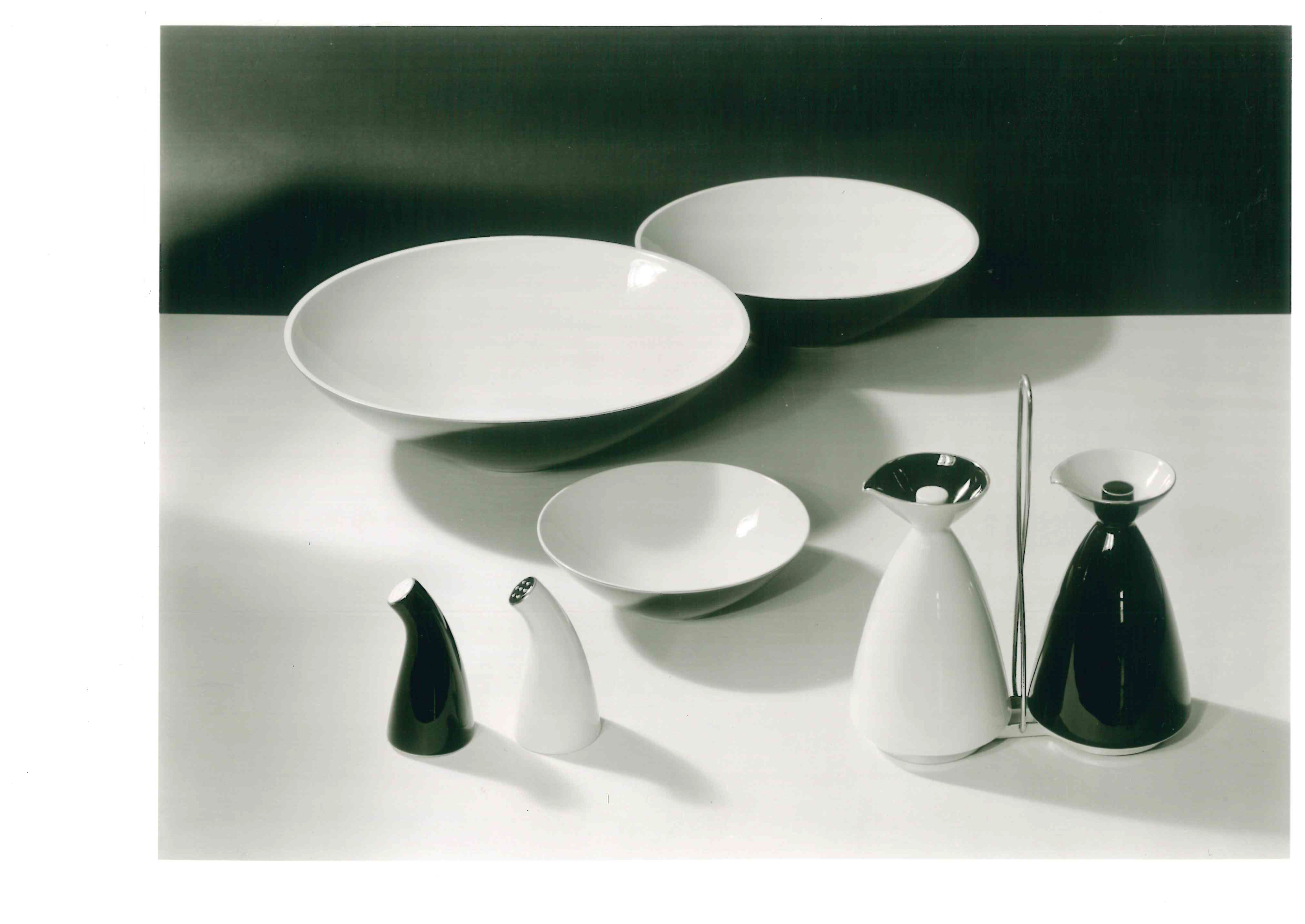

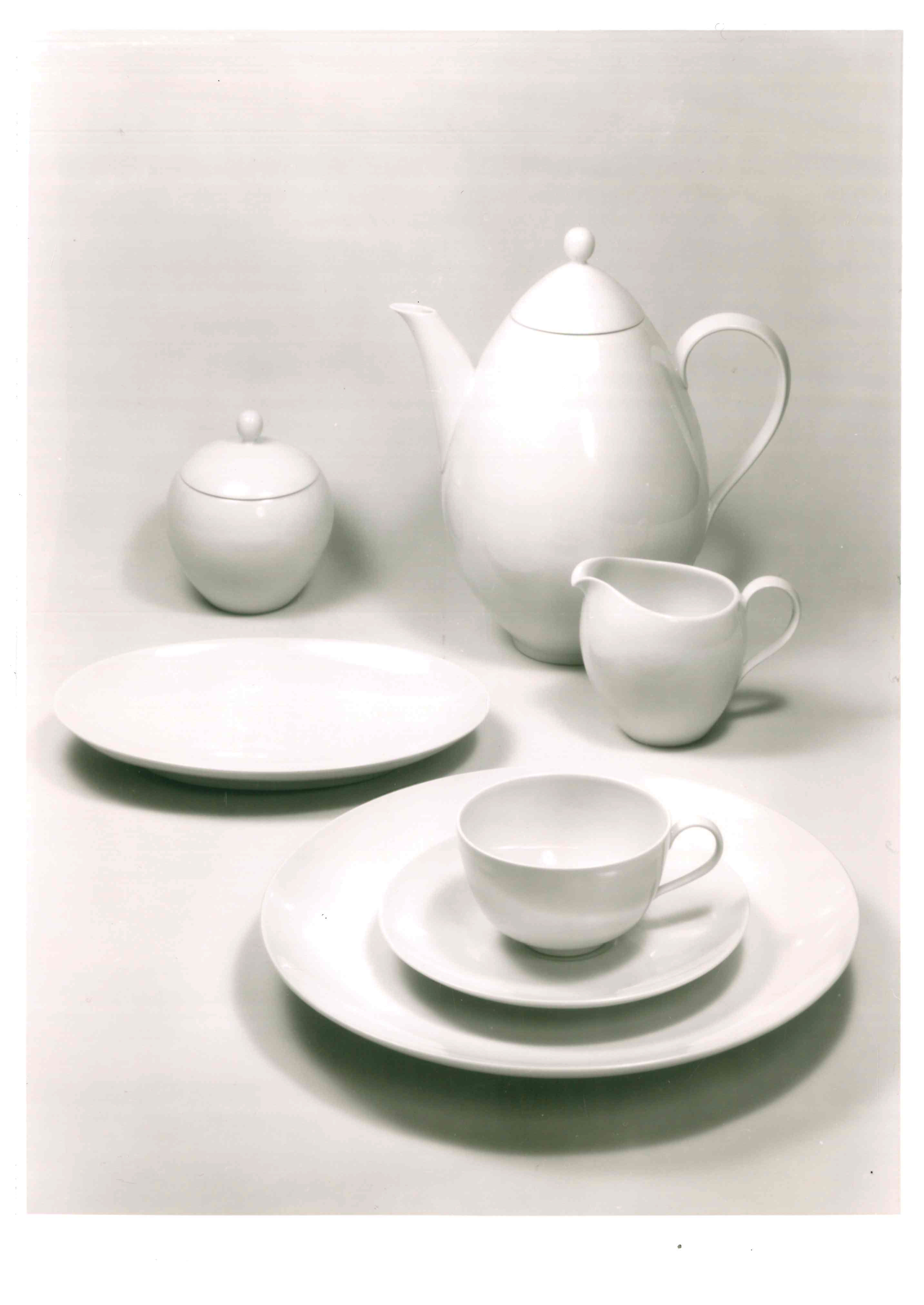

Looking back––now that Anni Albers has reached international recognition as a textile artist––one can speculate that the school’s curriculum, specifically the courses delivered by Friedrich Adler, and perhaps also by Maria Brinckmann 30 , did indeed exert some influence on the artist, even if only as a catalyst for the confrontation with the obsolete aim for decoration to be ‘timelessly relevant’. Even if the 22-year-old did scorn needlepoint as “sissy” or girl stuff, she nevertheless got to explore textile techniques and materials. This is where the founding program of the Bauhaus, which aimed to unite the arts and crafts, offered a way out: “Let us strive for, conceive and create the new building of the future that will unite every discipline, architecture and sculpture and painting . . .”, was published in April 1919, exactly two years before Annelise Fleischmann began to study at the Staatliche Kunstgewerbeschule zu Hamburg.“ Fortunately a leaflet came my way from the Bauhaus [on which] there was a print by Feininger, a cathedral, and I thought that was very beautiful and also at that time, through some connections—somebody told me— [that it] was a new experimental place . . . I thought, ‘That looks more like it,’ so this is what I tried.” 31 Redslob, daughter of Edward [sic! Edwin] Redslob––a German government official who had backed the cause of the Bauhaus, the experimental art school Walter Gropius was opening under the aegis of the Duke of Saxony in Weimar––told her about the new art school where all the crafts would be allotted equal performance, ornament cast to the wind, and function given a role of honor.” Weber 2020, p. 58. This story however lacks plausibility, since the older of the two daughters of Edwin Redslob, who was Reichskunstwart between 1920 and 1933 and a prominent supporter of the Bauhaus, was named Ottilie and not Olga, and born in 1914 (d. 2001). However, since as soon as April 1919 Gropius had the Bauhaus Manifesto with the Bauhaus program distributed throughout Germany in form of a flyer and also placed advertisements for his school in art magazines, the information may have reached Annelise Fleischmann through a different path. On the PR work of the Bauhaus see Cornelia Sohn, “Wir überleben alle Stürme”. Die Öffentlichkeitsarbeit des Bauhauses, Cologne, Weimar, Vienna 1997, p. 51.] Once in Weimar, Annelise Fleischmann no longer had to show interest in biomechanics or in constructive aspects of the plant and animal world as the base of design. From the techno-material matrix of weaving, she developed her graphic geometric abstraction 32 by means of which space was no longer decorated and interiors softly upholstered as mere “balm to the soul”. Textiles could now assume architectural functions and flexibilize space through the use of mobile room dividers.

This text was first published under the title “Sissy stuff, mainly needlepoint” - Anni Albers at Hamburg State School of Arts and Crafts by Materialverlag der HFBK Hamburg. It has been slightly revised for this publication.

Anni Albers, Gunta Stölzl, Bruno Streiff, Shlomoh Ben-David, Gerda Marx and Max Bill in and in front of the Bauhaus Dessau studio building, repro print, undated; original photograph, April 1927; photo: Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin

Testimonial by Anni Fleischmann; Photo: Archive of the HFBK Hamburg